Published: Apr 14, 2021

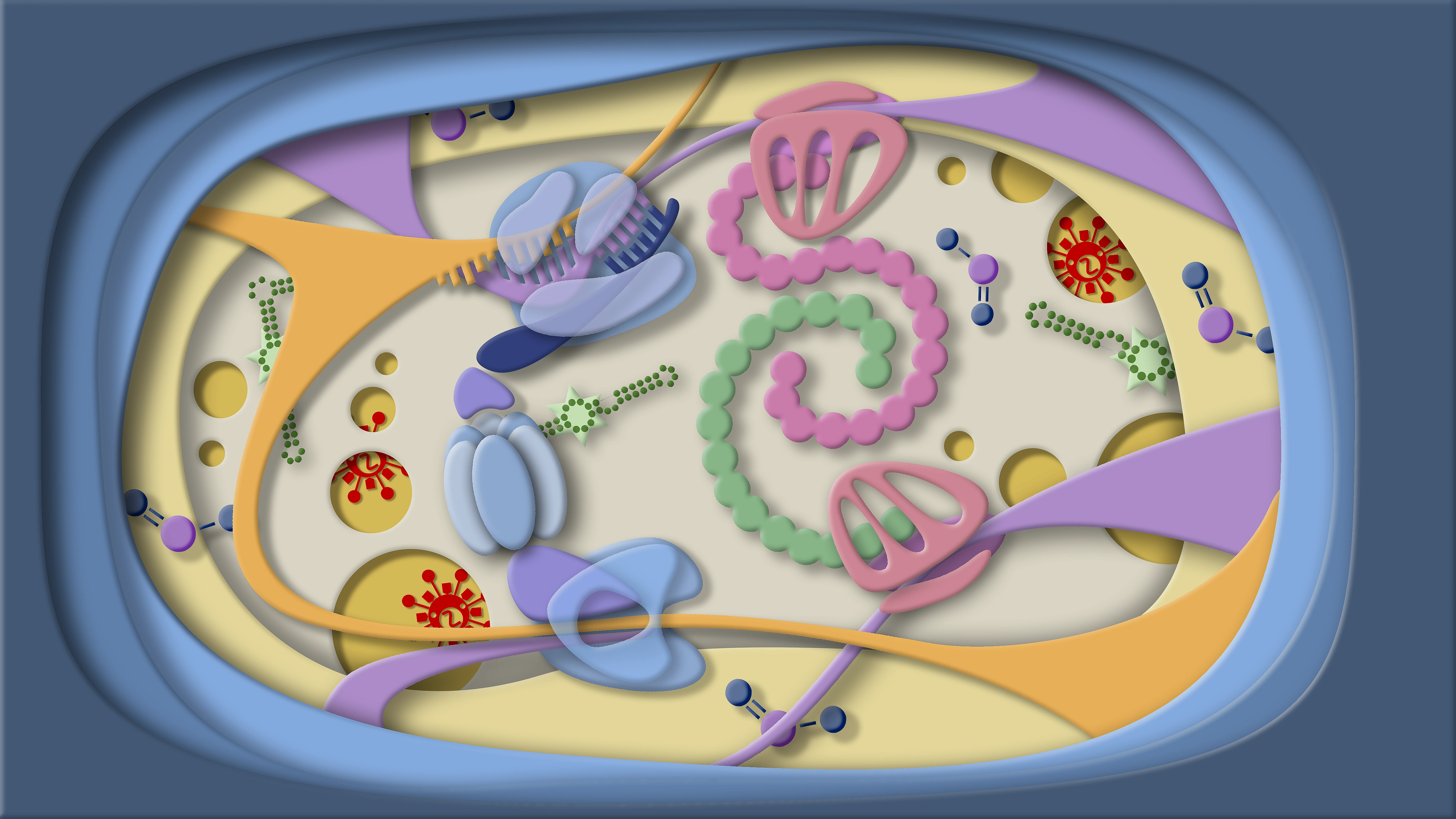

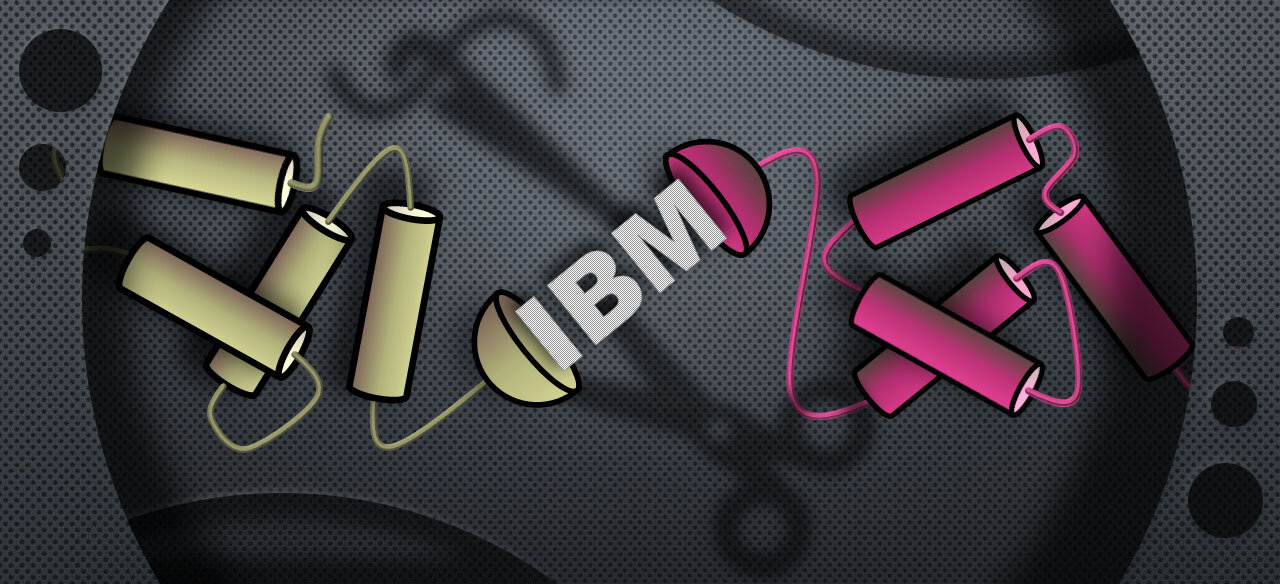

Intein-assisted Bisection Mapping (IBM) Credit: Baojun Wang

A new method of breaking and fixing proteins could speed the development of sophisticated computer-like circuits in cells that will pave the way to new biotechnology and medical advances.

The advance will make it easier to engineer cells that are programmed to behave as diagnostics or biological sensors—patrolling the body to detect disease or identifying toxins in the environment.

It could also provide a faster, cheaper and easier method of assembling large ‘designer’ proteins with many applications, such as antibodies or those used in vaccines or cell-based therapies.

The technique expands the synthetic biology toolkit, allowing proteins to be programmed to control the behavior of complex systems inside cells, creating defined pathways and signaling systems.

A key feature of more complex genetic circuits, that mimic those found in electronics, is the ability to build logical behavior—such as converting two signals into a response.

A team led by researchers at the University of Edinburgh developed a method to program proteins with this dual logic function, paving the way to the precision-level control needed in biocomputational circuits.

In cells one of the simplest logic behaviors is an AND gate function—this involves an input, the presence of two different molecules, which produce an output, activating or suppressing a gene.

This requires programming proteins, which regulate genes and control the cell’s functions. Breaking a protein-coding gene into two inactivates it and allows each to be tailored to receive different signals.

When both signals are received the genes are activated and two protein sub-units are produced which bind together, forming the original protein which activates or suppresses the gene of interest.

However a key limitation in building logic circuits in cells is that breaking protein-coding genes at random points can damage their function and prevent the protein from being reassembled later.

To tackle this the team harnessed moveable genetic parts, known as transposons, to find break points that protect the protein’s function and allow the two subunits to be joined together later.

Transposons, also known as jumping genes, are common in the genome and move around controlling how genes are used.

By harnessing the ingenuity of nature’s existing genetic toolbox, transposons allow scientists to test all the potential break points in a protein’s genetic sequence to find the sweet spot.

Previously researchers needed to rely on complex computer programs or laborious laboratory work to make educated guesses or test potential break points that will not destroy the protein.

The technique also offers researchers better control of the on-off switch in genetic circuits, as the reassembled proteins do not risk becoming partially active in the ‘off’ state, a common problem.

The advance builds on the team’s earlier work, creating a library of protein glues, known as split inteins, which act as ‘molecular velcro’ to seamlessly join protein sub-units together.

The process, known as protein splicing, allows very large proteins to be assembled from smaller units without disrupting the protein’s function.

Inteins are also part of nature’s toolbox, common in many forms of life, and form part of the protein production machinery in cells. They fine tune and modify proteins after they have been built.

The combined power of transposons and split inteins paves the way for scientists to more easily program proteins with the logic functions needed to build more complex genetic circuits.

The technique could also be used to design and mass produce very large proteins that have useful properties for medicine or industry, but are currently difficult or expensive to manufacture.

The study, published in Nature Communications, was funded by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship, awarded to Dr. Wang, and Leverhulme Trust. It involved researchers from Microsoft Research Cambridge, University of Turku and Zhejiang University.

“We developed a new powerful method for engineering functional split proteins by combining the advantages of two revolutionary biological tools, the transposon and split intein, to rapidly locate all suitable breaking and recombining sites of a target protein. This tool will help unlock many applications by splitting proteins in biotechnology and medicine such as design of biocomputing programs in cells, reduction of a protein’s harmful basal expression and engineered proteins that are responsive to new controllable signals.”