Published: Nov 30, 2020

In the past year, things have been complicated for me. I had my first baby last November. It is joyful and exciting to see how the little thing grow up so fast and try his best to interact with everyone and explore everything, but raising a child, particularly at early stage and during this pandemic when things are not going well, has posed big challenges to my emotions and physical health, as well as to my career. I wouldn’t have reached this far without any support, and I am very grateful that I have an excellent supervisor, a great team, a cheerful husband and a loving mother. Here, I would like to thank everyone that has been always supportive during this difficult time!

Many research studies come from small inspirations and ours is no exception. It started two and a half years ago when we were preparing another manuscript (on whole-cell biosensors and cascaded amplifiers) for Nature Chemical Biology[1]. This is where the inspiration and motivation for the DNA sponge project came from.

When we were studying the impact of cascaded amplifiers on biosensors’ performance, we also tested whether they could cause notable burdens on the host cells. We observed that for one cascaded amplifier (HrpRS-RinA-ECF11), having the three-layered amplifiers in a single low-copy number plasmid negatively affected growth. Surprisingly, we found that moving the last amplifier’s output promoter to a high-copy number plasmid not only improved the sensor’s output readout, but also recovered the host cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 9b1). This was contradictory to our general knowledge, in which high-copy number plasmids should impose higher burden on the host cells than low-copy number plasmids, if there are burdensome elements. This raised the questions of ‘how it happened’ and ‘what was the regulation mechanism behind it’. Moreover, we found that such effect did not occur for a different cascaded amplifier circuit with the same elements, but where the last two amplifiers were swapped (HrpRS- ECF11-RinA; Supplementary Fig. 9a1). This led us to believe that the change in burden was specifically related to the last amplifier, and that the regulation mechanism must be hidden somewhere between the last amplifier’s activator (i.e., ECF11) and the high-copy number reporter plasmid used. So, what was it?

My supervisor, Dr Baojun Wang, often says that inspirations always come from learning other people’s work.

It is true! Particularly in this case, we found potential answers in another paper published in Nature, where “DNA sponges” were used to improve the function of a repressilator[2]. In that work, the authors used the promoters responding to repressors TetR, LacI and cI as the “DNA sponges” to decoy away the excess repressors, enabling the precise and long-term operation of their synthetic clock. From there, we realized that in our cascaded amplifier, the ECF11’s cognate promoter Pecf11 not only played a role in activating the reporter GFP expression when bound with ECF11, but also “sponged” the ECF11 during the process. Besides, we found the ECF11 itself was very toxic to the host cells (Supplementary Fig. 31). Together with another paper’s suggestions that the toxicity of ECF could derive from RNA polymerase (RNAP) competition for native RNAP with host sigma factors and/or from aberrant gene expression[3], we then hypothesized that the recovery of cell growth might be due to ECF11 sponging. This would prevent most of the ECF11 from interfering with the host’s native transcription system and harming the cells. Encouraged by Baojun, we decided to study the DNA sponge and validate our hypothesis.

Small ideas are like snowballs that can get bigger if they keep rolling.

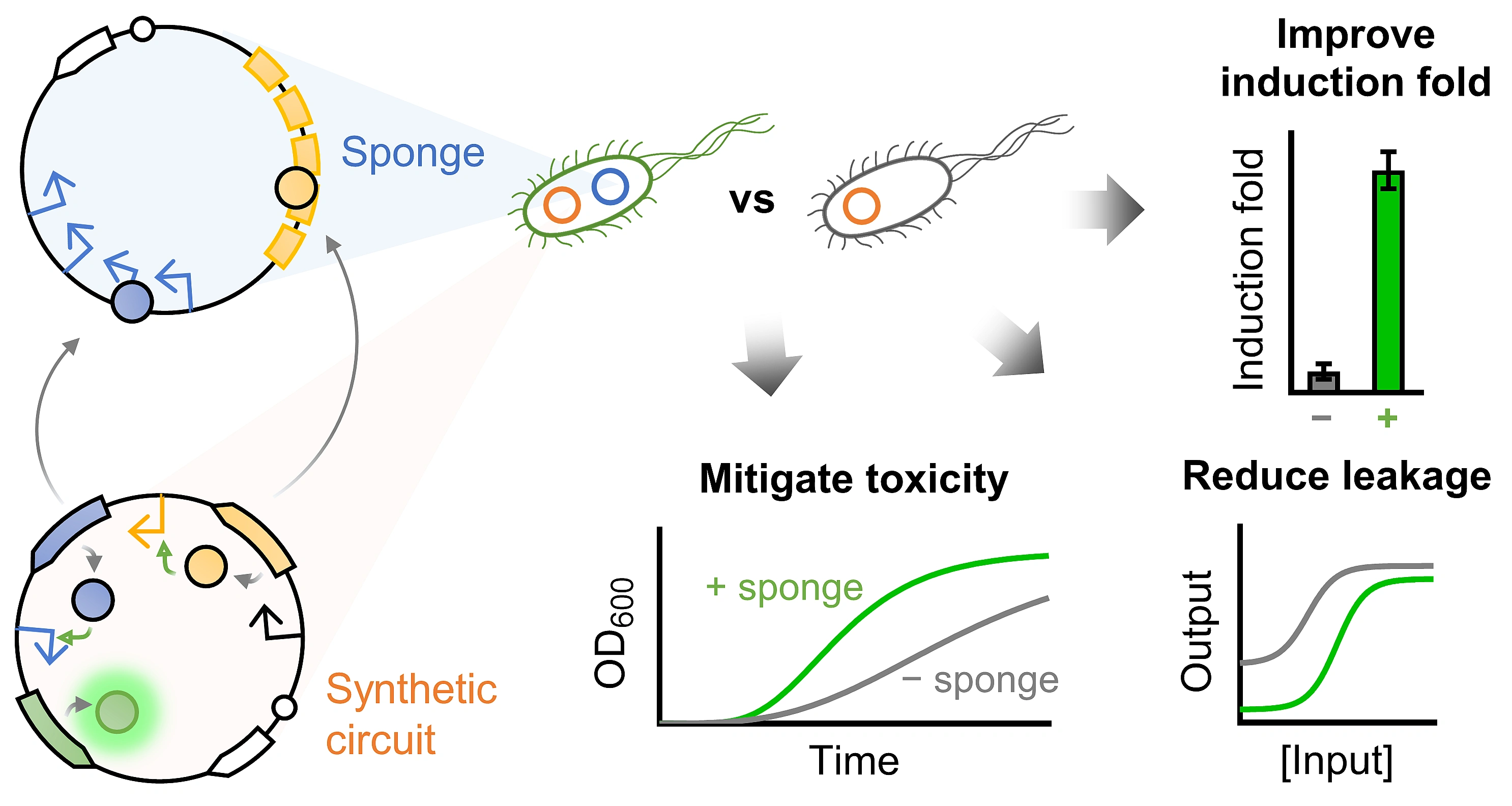

By reading more publications about DNA sponges or decoy DNAs, we became more and more interested in how they reshaped gene circuits’ responses, buffered gene expression noise and even contributed to gene therapy. By gathering all these ideas, we thought we could study the DNA sponge phenomenon more deeply, not only in relation to its impact on cellular burden, but also to get a more complete picture on how it could regulate the performance of gene circuits (Fig. 1). As a result, we started the study from simple to complex gene circuits and from single to multi-layered sponges. We were very excited to find out that DNA sponge could actually regulate gene circuits in a systematic manner, including decreasing basal leakage, improving output readout and induction fold, shifting responding input range and mitigating toxicity caused by the burdensome proteins. More interestingly, a single sponge could do most of these jobs at the same time without causing further burden to the cells!

We are pleased to have our work published in Nature Communications, and I am grateful that we have grasped the small inspiration from the very beginning and expanded it to the present stage. Although all the work was done in Escherichia coli, DNA sponges may also be applied to other prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. We expect this simple yet versatile tool will benefit many bioengineering researchers with their gene circuits optimization tasks as well as providing a way to mitigate the toxicity of burdensome regulatory proteins for a variety of applications in biosensing, biotherapy and biomanufacturing.

Our paper:

Wan, X., Pinto, F., Yu, L. & Wang, B. Synthetic protein-binding DNA sponge as a tool to tune gene expression and mitigate protein toxicity. Nat Commun 11, 5961 (2020).

Reference

- Wan, X., Volpetti, F., Petrova, E., French, C., Maerkl, S. J. & Wang, B. Cascaded amplifying circuits enable ultrasensitive cellular sensors for toxic metals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 540–548 (2019).

- Potvin-Trottier, L., Lord, N. D., Vinnicombe, G. & Paulsson, J. Synchronous long-term oscillations in a synthetic gene circuit. Nature 538, 514–517 (2016).

- Rhodius, V. A., Segall-Shapiro, T. H., Sharon, B. D., Ghodasara, A., Orlova, E., Tabakh, H., Burkhardt, D. H., Clancy, K., Peterson, T. C., Gross, C. a & Voigt, C. a. Design of orthogonal genetic switches based on a crosstalk map of σs, anti-σs, and promoters. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9, 702 (2013).